The UK Property Market 2023: Beneath the Headlines

Media reports play a big part in shaping public opinion. One of the most compelling examples of this is the way that recent articles have influenced popular perceptions of the state of the UK property market. Dramatic editorial pieces about rising interest rates paint a dark picture of a market that’s in crisis. However, if we look beneath the attention-grabbing headlines, it soon becomes clear that the reality is much more complex, more varied and, in some regions, considerably more promising that some journalists would have us believe.

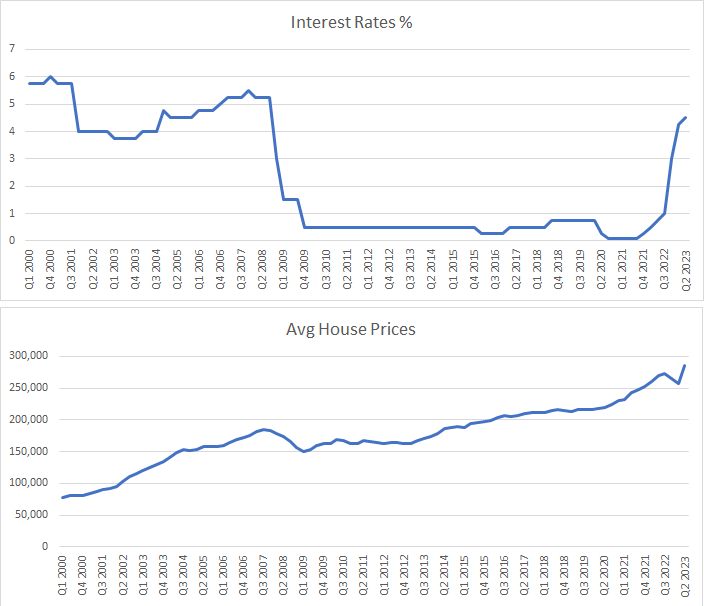

For example, take a look at the following graph. It shows the long-term trend in UK house prices, according to the Land Registry and the Office for National Statistics.

In recent months, newspapers have devoted much attention to individual house price indices, some of which have shown small month-on-month dips in average values. (The June index from Rightmove, for example, notes a monthly drop of just £82, which compares to its quoted average property price £372,812.) On this graph, any such dip would barely register. What’s more, according to the most recent (April) data from ONS – widely regarded as the definitive source of British house price data – values are still 3.5% higher than they were 12 months previously. Indeed, an average of all the major house price indices (lenders, estate agents and the ONS) shows the same thing: that prices remain fractionally higher now than at the same time last year. And, without question, they are substantially ahead of where they were in June 2021.

Over the longer term, capital growth rates have considerably outpaced inflation and although the market is witnessing a temporary reversal – the indirect result of unusual external factors such as Covid and the Russian invasion of Ukraine – the laws of supply and demand suggest that the more familiar upward trend should gradually reassert itself.

As we noted in our May Property Market Update, all the major sources, including the Bank of England, the Office for Budget Responsibility, the International Monetary Fund and others are predicting that inflation will fall over the coming months. The Bank of England expects CPI inflation to drop to 5.1% by year-end while the OBR expects it to fall as low as 2.9%. As it continues to decline towards the Bank’s 2% target, so the real-terms returns on capital growth should gradually improve.

Moreover, longer range house price forecasts look respectably positive. Savills, for example is predicting growth of 2.5% in 2024 and a further 4.5% in 2025. If these projections are anything like accurate, then capital growth should once again outpace inflation and, thus, begin to deliver real-terms growth within just a couple of years.

Property investment has always been a business that is most sensibly viewed in the longer term, and shorter-term dips such as we face today tend to get swallowed up by the broader trends. One inescapable fact of the UK residential market is that demand massively outweighs supply. That’s true in both the house-buyer market and the rental market, and it’s why values have tended to rise so significantly over time, as the graph and the ONS data show. Gloomy opinion pieces certainly attract attention, which helps to sell newspapers and journals, but they also make it easy to miss the bigger picture.

UK Property and Interest Rates

When it comes to hiding the big picture, there is perhaps no better example than the subject of UK interest rates. In June, the Bank of England’s decision to raise the official Bank Rate elicited countless downbeat articles, many raising the spectre of repossessions and a market collapse. This sort of media attention makes it very easy to forget that the current rates of interest remain very modest by historical standards. It is only in comparison to the most recent, very exceptional period of unusually low interest rates that today’s base rate of 5.0% looks high. In reality, it is nothing remotely unusual, as the following graph shows.

In the late 1970s, the Bank Rate peaked at 17%, but house prices continued to increase, from £4,378 in 1970 to £23,497 as we entered the ‘80s.

1970 - 1980

And in the early ‘90s it was back up to 15%, having never dipped below 8.0% during the intervening years, and although we can see a slight drop in house prices towards the end of this period, they then started to rise again in the latter part of the ‘90s.

1988 - 1992

Between 2000 and 2008, it typically ranged between 4% and 6%, and was only slashed at the end of that period in response to the global financial crisis. It was after that, in the long period of ‘cheap money’ that followed, that the idea of ultra-low interest rates began to be normalised. That has certainly made recent rates rises unpalatable, but in a historical context, the UK is still experiencing what would normally be considered to be low to average rates of interest. It’s no recipe for calamity.

2000 - 2023

Such statements don’t make for hugely interesting headlines, of course, but there is a danger that sensationalism can hide some important facts. A recent article in The Times makes a similar point. In this case, it refers to what it describes as ‘doom-mongering’ by many UK media outlets. It highlights how quick they were to report that repossessions were “24% higher” in Q1 2023 than they had been at the same time in 2022. Crucially, however, it adds that although the figure looked dramatic on the face of it, it actually represented only 139 additional homes. The simple fact was that, UK-wide, the total number of repossessions rose from 579 to 718. “Seven hundred is not nothing,” observes the paper, “but not a lot for a country the size of ours, and still 45 per cent below where they were trending before the pandemic. In 1992, banks took back the keys for 75,000 homes. Broadly, repossessions are at 40-year lows.”

A More Secure Foundation

Some journalists will be happy to jump aboard the bandwagon and play to people’s fears of repossessions but, in reality, such actions are always a last resort for lenders. It is costly for banks and building societies to take that step, both in financial and reputational terms. It means lost income on mortgage payments, unwanted repair costs and a big administrative burden, to say nothing of building ill-feeling amongst borrowers. Lenders will typically do all they can to avoid that, and not only for commercial reasons but also because they are specifically obliged to do so by the Financial Conduct Authority. A short-term readjustment – such as switching to an interest only mortgage – will generally be a far more attractive option for all concerned.

Another important reason why higher interest rates shouldn’t precipitate large-scale market disruption is that lenders have adopted much stricter application criteria since 2008 and the global financial crisis. Mortgage stress-testing has ensured that most borrowers should still be able to cope with a succession of rate rises, albeit they may face considerable belt-tightening for a while.

Of course, that ability to cope depends on how high mortgage rates eventually go, but there are two clear reasons to expect the market to remain resilient. First, as we’ve discussed, the UK has been here before, the base rate having stayed much higher than it is now – and for whole decades at a time. True, house prices were comparatively more affordable at the time, so borrowers today may well feel more stretched, but lenders have generally been very prudent and cautious about the amounts they have allowed home-buyers to borrow.

The other reason to expect the market to remain steady is that interest rates are most unlikely to rise considerably further or for a very protracted period. The Bank of England is using interest rates as a tool to control inflation but it also recognises that higher rates act as a deterrent to economic growth. It’s a bitter economic medicine, so as soon as it looks as though the underlying rate of inflation is back under control, it will want to lower the base rate again in order to allow the UK economy to recover. The forecasts are that the Consumer Prices Index will be back to the target rate of 2% towards the end of next year (Q4 2024) and those closer it gets to that figure, the more pressure the Bank will feel to reduce interest rates again.

Not All Investors are Borrowers

Regardless of their more general impact on the property market, higher interest rates are undoubtedly an unwelcome change for all those investors who require new finance to fund their purchases. However, for those who can afford to buy outright, or for the many ‘accidental landlords’ who acquire a property through inheritance, marriage or new personal partnerships, the present conditions are far more amenable. Without mortgage interest costs eroding profitability, the net returns on rented property can be very good indeed.

Capital growth rates may not be spectacular at present but the longer-term prospects for growth are good. In its April Housing Insight Report, Propertymark notes that its member agents saw an average of 70 new prospective buyers registered per branch, whereas the number of new homes available for sale had stayed steady at just 10 per branch. That huge disparity between demand and supply is reportedly 35% greater than at the same time in 2022 and looks set to continue. For so long as it does, it should continue to apply upward pressure to asking prices.

However, even before capital growth delivers any meaningful returns, rental returns will almost certainly ensure that residential property remains a worthwhile investment. The latest UK Rental Market Report from Zoopla suggests that average rental values have risen by 10.4% year on year, which is considerably faster than the CPI rate of inflation.

As in the home-buyer market, rental values are being driven higher by an imbalance between demand and supply. In the same Housing Insight Report, Propertymark notes that the number of new prospective tenants registering per member branch rose to 118 in April. This figure is 24% higher than in April 2022 and it compares against a typical supply of just 9 rental properties available per member branch. The inevitable result is more intense competition between tenants and that, in turn, tends to drive up asking rents.

In the short term, the continuing cost-of-living crisis should present tenants with more concerns about affordability, so rental values cannot escalate forever. Rents have risen faster than average earnings for many months now. However, with no end in sight to the gap between supply and demand, all the signs are that rental incomes will remain both dependable and rewarding for investors.

Supply of Rental Property

Another go-to headline for many property market journalists is the supposed ‘exodus’ of landlords from the sector. The popular narrative is that droves of landlords, deterred by rising mortgage costs, are selling up and leaving the market. However, the reality is much more nuanced and, as the latest rental market report from Zoopla suggests, it is actually no exodus at all.

Zoopla states that it does not “expect to see a worsening in supply, and talk of an exodus of landlords is being somewhat overdone.” It concedes that there is “a steady, constant flow of private landlords selling up – this has been the case since 2018 – but it is not accelerating. At the same time, there remains continued new investment in rented homes, mainly from corporate and institutional landlords. The net result is no change in the number of private rented homes since 2016.”

The supposed exodus may have no clear basis in fact but one interesting point in the Zoopla report is that more landlords do appear to be selling up in Britain’s higher-priced markets; in those cities and wealthier suburbs where asking prices are unusually high and where it is therefore most costly to remortgage. It writes that “our data on landlord sales shows a clear concentration in London and the South East, accounting for 51% of landlord sales. These regions have high capital values and low rental yields. This makes the economic situation tougher for landlords in the face of rising mortgage rates, as profits are reduced, especially for higher rate tax payers.”

By contrast, it’s much harder to discern any clear pattern of sales by landlords across the rest of the UK. Where private landlords do sell, for whatever reason, the bulk of properties tend to be quickly gathered up by institutional investors and larger portfolio-holders; in short, by experienced professionals who recognise the long-term strength of residential property as an investment asset. In many cases, as we shall see, they are focusing their acquisitions on the UK’s more affordable regional markets.

Regional Patterns

When it comes to capital and rental growth, UK averages tend to dominate the headlines. It is usually the national mean that commands most attention, but for investors in the real world, such figures are all but useless. The performance of residential property varies so much by type and location that even regional data can only afford a very limited insight into where the best opportunities might be found.

Nevertheless, regional figures do at least help to narrow the search and when we look at reputable sources, such as the June House Price Index from Rightmove, it becomes evident that, by and large, the country’s more affordable regions are delivering the fastest rates of capital growth.

The agency reports that average values rose by 1.1% year-on-year across the UK as a whole but that they rose by 3.6% in both Scotland and the North West. Next came another lower-priced region, the West Midlands (where values rose by 2.5%), followed by Yorkshire & Humber (2.4%). On the measure of monthly growth, the modestly-priced North East led the field with a figure of 4.9%, followed by Wales (1.8%) and the West Midlands (1.1%). In short, where absolute values tend to be lower, buyer sentiment seems to be more positive and the market retains more capacity for growth.

When it comes to rental values, there is less evidence of a North-South divide, although (with the exception of London) lower-priced markets still tend to predominate. According to the latest Homelet Rental Index, the strongest regions for rental growth have been Scotland (13.4%), Greater London (11.3%) and Wales (10.9%). However, rental values have generally been holding strong across the UK; Homelet reports that all other regions except the South West and the North East produced average annual rental gains of 8.9% or above.

Zoopla’s June Rental Index suggests a broadly similar pattern. It names the frontrunners as London (13.5%), Scotland (13.1%) and the North West (10.5%), with the North East and the South West again lagging, with figures of 8.0% and 7.1% respectively. Zoopla also names some of the country’s top cities for rental growth; Edinburgh, Manchester and Glasgow head the table, followed by Aberdeen, Southampton, Cardiff, Birmingham and Nottingham.

Conclusion

The cost-of-living crisis was always going to affect the property market by constraining people’s disposable incomes and putting more emphasis on affordability. Inflation has spread household budgets ever more thinly and left both buyers and tenants with less to spend on moves to bigger or better-located homes.

A gradual decline in capital values has been the logical outcome from all of this; houses are generally the most expensive purchases that families ever tend to make, so (after non-essential luxury goods) they are one of the first commodities to feel the price pinch.

However, while prices have been rising, so have average earnings, which means that the affordability gap is not as wide now as many would have expected. That goes some way to explaining why, despite soaring inflation, a rising Bank Rate and the highest tax burden in at least a generation, average annual price growth has so far merely levelled out.

Affordability issues also explain why the country’s traditionally more affordable markets – broadly speaking, those outside London and the Home Counties – are holding their values better, attracting more buyer interest and displaying the greatest capacity for price growth. They are also tending to see very robust growth in rental values, fewer void periods and better yields.

Another key reason why the UK property market has avoided the crash that some predicted towards the end of last year is the most enduring factor of all: the continuing excess of demand over supply. Far more buyers and tenants are looking for homes than there are actual properties available. That imbalance isn’t going to go away and, while it remains, it will always tend to exert upward pressure on prices.

Headlines have focused on the downside risks arising from higher interest rates and the cost-of-living crisis but they shouldn’t be allowed to mask what is, in reality, a very chequered picture. Investment returns vary massively by location, property type and local market demand, and well-chosen developments can certainly still produce solid real-terms rewards.

* * *

To find out more about investment opportunities in residential markets across the UK, please call our advisory team on 01244 343 355 or for a free no obligation call with one of our experienced consultants, please complete our investment enquiries form below